In many North American communities, the prevailing expectation is that driving is the primary, if not the only, way to get around. This assumption has shaped our transportation infrastructure in ways that often go unnoticed but have significant impacts on accessibility and livability. Streets and even whole suburban neighbourhoods are designed with cars in mind. Often neglected are the needs of pedestrians, cyclists, and public transit users, basically anybody who isn’t in a vehicle.

This car-centric approach can lead to a range of issues, from increased traffic congestion and pollution to reduced safety and mobility for those who do not drive. It can also cause issues when road infrastructure eventually needs to be replaced or upgraded, because a single road closure (for a crash or construction) in the wrong place can block traffic until it’s cleared up. With a more diverse transportation network, people can walk or bike past construction to nearby amenities or take the bus for longer journeys. And for people who don’t want to do that, driving around the blocked streets will be easier for them too. By examining the consequences of this expectation, we can begin to understand the importance of creating a more balanced transportation network that serves all members of the community.

Expectations play a crucial role in shaping urban transportation options. Currently, throughout the continent there is a widespread expectation that cars should be able to navigate almost anywhere with minimal delay and in the shortest possible time. This assumption heavily influences how transportation infrastructure is designed and maintained. It is extremely rare in North America to find communities where car isn’t #1 and any other transportation options are typically orders of magnitude less important in terms of planning

There are suburban streets (including the one my house is on) in my community and suburb where there are no sidewalks at all. When the community was built, the expectation was that everyone would be driving everywhere, and if people wanted to leave their house for a walk literally anywhere, they could walk in the street with the cars.

Yes, It’s Bad

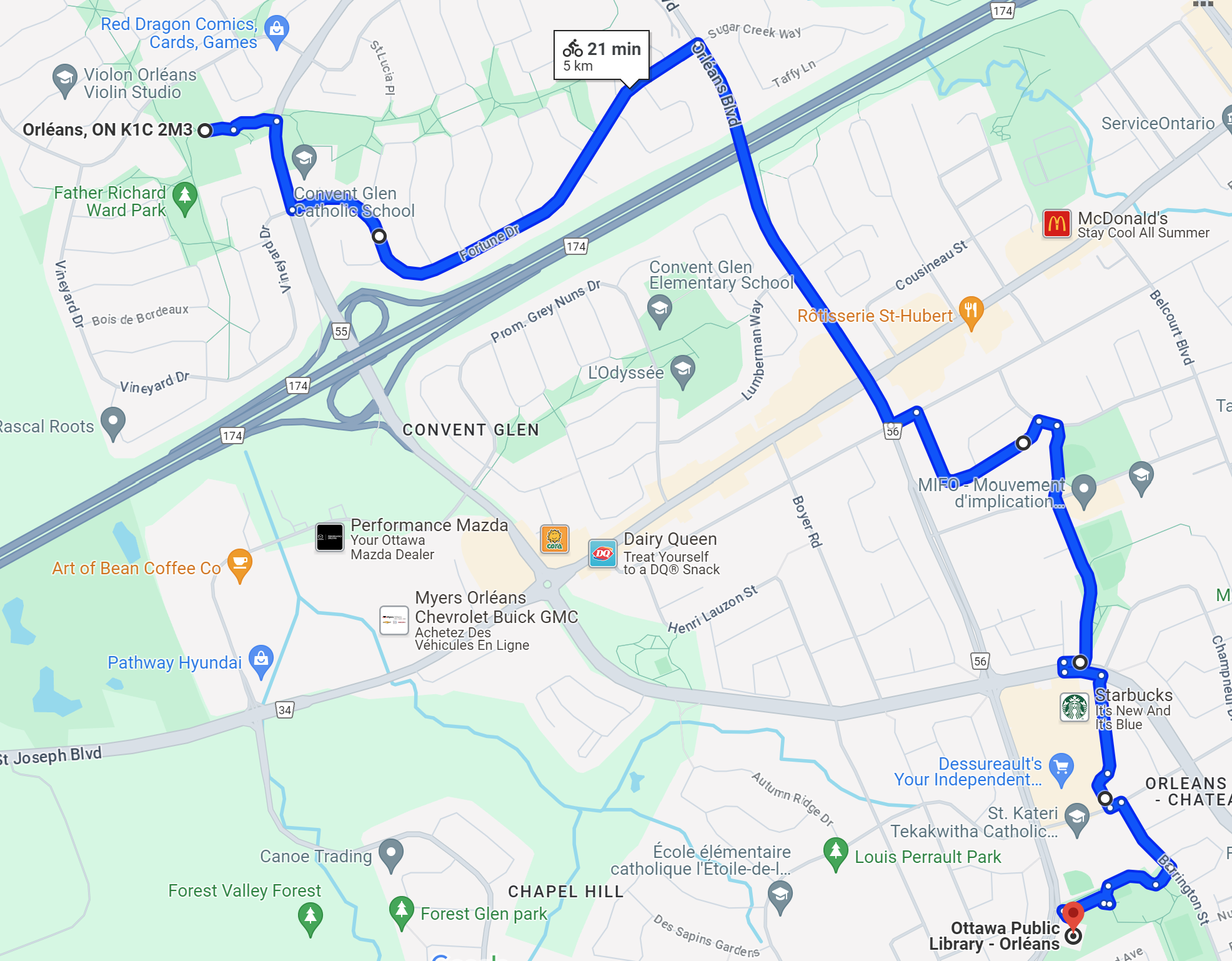

I have stood at my window and watched as an SUV pulls up to the curb (I live across from a lovely park, for which I am very grateful), and watched a mother get out of the car. She got a bike out of the trunk and her son out of the back seat. This woman (who I absolutely do not know) felt compelled by our road and/or path network to teach her child to ride a bike far enough from where they live that she couldn’t get there on foot, or possibly didn’t feel safe doing so. This is a symptom of community infrastructure that fails to meet the needs of its residents.

The system we’ve created and continue to rely on EXPECTS almost exclusively people in cars in many places. We give vehicles a literal red-carpet experience to move through our neighbourhoods, but don’t afford any of the same luxuries to people walking, cycling, taking the bus, or using any other mode of transportation.

If we as a city and community can escape the car-centric design bubble and apply the same expectations we have for cars, trucks, and other vehicles to other modes of transportation, such as cycling and public transit, we can create a more inclusive and efficient transportation network. When a city anticipates that its transportation network will be used by a variety of modes—cars, pedestrians, cyclists, strollers, scooters, or buses—it becomes easier to design and prioritize infrastructure that accommodates all users, as well as to justify diversifying the network further.

In truth though, this is more nuanced than just a checkbox ‘there’ or ‘not there’ for sidewalks, bike lanes, bus routes, paths, etc. There are degrees of expectation for transportation infrastructure, and here again we see huge disparities in many suburban places in North America.

We have more than our fair share of spacious, 4-lane roads with speed limits of anywhere from 40 up to 80 kph. Lots of these roads are often lined with massive parking lots leading to shops with almost nowhere for people to exist in between. This is because the whole system is designed for the expectation that people will drive ‘there’ (wherever ‘there’ is), do whatever they need to do, and drive home. Sidewalks along these roads are basically never more than a few feet wide, and you sometimes (but definitely not always) get a 2–3-foot asphalt or grass buffer from the roads.

If a transportation network is instead designed with the expectation that pedestrians, cyclists, and buses will use it, the infrastructure must therefore be maintained according to those expectations, lest it be considered inadequate. This means ensuring routes (including paths and bike lanes, painted or separated) are clear of snow, free of obstacles, and safe for use. It means sidewalks should be wide and friendly and not right next to fast-moving and loud car traffic. It means buses and other public transit should be able to follow their routes without getting stuck in car traffic, and should offer frequent service and with a variety of local and commuter routes.

By setting these expectations, cities can create a more resilient, reliable, and user-friendly transportation system for everyone. Once this has started to change, when users can trust that their chosen mode of transportation is supported by the transportation infrastructure, they are more likely to get out and try to use it confidently. This almost inevitably leads to increased usage of alternative transportation options, reducing traffic congestion and promoting a healthier, more sustainable urban environment.

But It’s Cold

These expectations continue to be true regardless of the weather. Right now, for example, it’s mid-January and we’ve just experienced a pretty cold snap, with weather between -10 and -25 Celsius for the last 3-4 days. At the moment in Orleans, where I live, we have had to bug and poke and plead to get some of the main community paths cleared in the winter. This was only possible due to recent asphalt upgrades on the paths to fit them for modern standards and to have the mini-plows drive over them without ripping up the pavement.

However, what minimal active transportation networks we have access to in better weather, other than the paths I just described, are not maintained at all. When transportation infrastructure is maintained in the winter according to the expectations of its users, people use it. This is true of cars and roads, and also the other transportation options we’ve been talking about. When there is a blizzard in Ottawa, road crews ask drivers to stay off the road outside of emergency situations, because driving in these conditions is less safe than once roads are cleared. Without maintenance in the winter when necessary, none of our transportation options are safe or accessible.

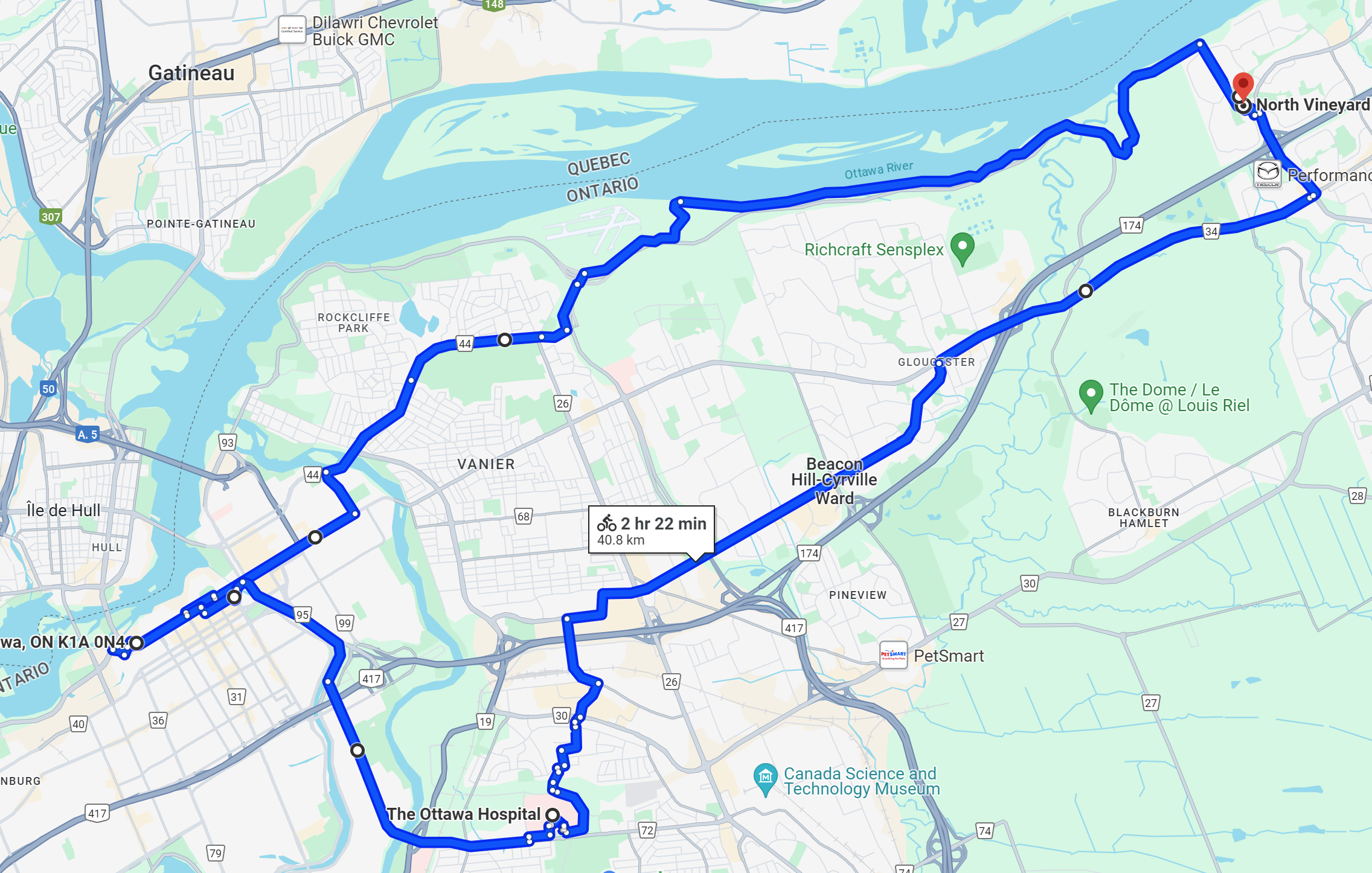

If the city took the transportation network seriously all the way from Kanata to Orleans, with separate and safe infrastructure for people outside of cars, maintaining that infrastructure through the year could be an easily achievable goal. This would have the added benefit of helping us mitigate the effects of climate change and traffic congestion (and more) over time. It is not and probably never will be for everyone to cover long distances in the winter on foot or on bike, but for short (2-5 km) trips unless it is extreme cold warning levels of cold, being on a bike is actually quite nice. We are so used to being cold in the winter because we are using no energy to keep ourselves warm, but on a bike, you’re moving and it’s much easier to not get cold, especially if you’re prepared for it.

If you spend your days driving around in a car in the winter, you’re much less likely to be prepared to be outside for more than a couple of minutes. If you’re dressed to be outside though, it truly doesn’t take much to stay warm, especially if you’re moving on foot or by bike. Combine changes to the transportation network with zoning changes to slowly allow small businesses to build and operate inside our single–family-home-exclusive neighbourhood, and it is certainly much easier to imagine running errands and getting around the community without relying on a car.

Setting clear expectations for diverse transportation modes and maintaining the infrastructure to support them can transform urban transportation networks. By doing so, cities can ensure that all users have access to safe, efficient, and reliable transportation options. This is not something that is likely to change overnight, but when presented with the opportunity as a community, we should jump at it. Funding for future-thinking projects like this don’t come around often.

More on the Gaps in Infrastructure

More on the Gaps in Infrastructure